March 19, 2021

This Shabbat: Parshat Vayikra

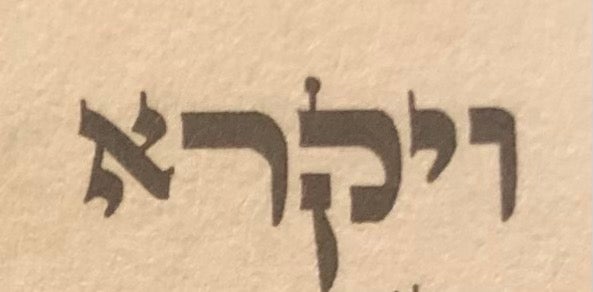

This week’s parsha begins the way many weekly portions do, with God speaking to Moses. The Torah tells us, “And God called to Moses and spoke to him out of the Tent of Meeting.” It all seems like a pretty ordinary beginning - until you take a closer look at the very first word, “Vayikra” - “And God called.” Oddly, the last letter of the word, the aleph, is smaller than all the rest. It looks like this:

The Ba’al HaTurim, a fourteenth century Bible commentator, explains that the aleph is smaller than the other letters due to Moses’ humility. As Moses was writing down God’s words in that first Torah scroll, he was uncomfortable with writing that God called out specifically to him. By shrinking the aleph, Moses hinted at a different meaning for the word. Without the aleph, the word reads “vayikar,” which means “and God happened upon.”

The Ba’al HaTurim’s interpretation teaches us something about leadership. Moses, who was chosen by God to lead the Children of Israel, was a reluctant leader from the beginning. When God first speaks to Moses from the burning bush, Moses demurs God’s call to lead, saying that he is not worthy. And now, Moses embeds his humility regarding his relationship with God into the very words of the Torah that God has given him. Good leaders, Moses is teaching us, must not allow their position to go to their heads. They must always remember their frailties and their humanity so that they may lead with compassion and integrity.

This message about leadership is particularly potent coming at the beginning of the Book of Leviticus. Unlike the books of Genesis and Exodus, which are replete with narratives about our forefathers and foremothers and about the birth of the nation of Israel, Leviticus has very few narratives. Instead it is filled with laws upon laws which are meant to govern the ritual and interpersonal lives of the Jewish people. A humble leader understands that the laws are not about fealty to her or him, but are rather about elevating society to a more just, moral, and safe place. Such a leader is able to transmit laws in a way that people can understand their importance and therefore follow them.

Each of us takes leadership roles at times in our lives. Whether in our professional, communal, or personal lives, we are in positions where we must explain and enforce rules that keep our communities - large and small - functioning as best as they can. Let us internalize the message conveyed by Moses and make sure that we wear the mantle of authority with compassion and enormous humility, and in so doing, keep our communities knitted together with a sense of common purpose and shared values.

For Shabbat Table Discussion:

- Can you think of a leader whose humility helped her/him lead more effectively? How did that play out?

- Are there times when humility is the wrong message for leaders to transmit? When and why?

- What does it mean to explain and enforce rules and laws with humility? Can you think of examples?

This Week in Jewish History

March 25, 1911 - The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

Until September 11, 2001, one of the deadliest days in New York City history was March 25, 1911. On that day, a fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory in Lower Manhattan, trapping 500 workers who were manufacturing ladies’ blouses in the factory that day and killing 146 -- 123 women and girls and 23 men. The factory, housed on the top three floors of the ten-story Asch building, employed hundreds of workers in the making of ladies’ blouses, also known as shirtwaists. Most of the workers were young, female Jewish and Italian immigrants. The working conditions in the factory were abysmal. The owners of the factory, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, did not permit workers to unionize. Exit doors were kept locked during the day to prevent workers from taking unauthorized breaks and there were not adequate fire escapes, nor were there alarms or sprinklers. The factory floors were littered with flammable fabric scraps, and once the fire broke out - likely in a trash bin filled with two months worth of such scraps, it quickly overpowered the factory. Some of the workers were able to escape via the freight elevator or the staircases, but those options quickly became unusable due to the spreading fire. Dozens fled to the roof while they were able. Although the fire department arrived quickly, their ladders were unable to reach higher than the seventh floor of the building. Many workers began to jump out the windows to escape burning to death as horrified spectators stood helplessly watching in the street. One reporter, William Gunn Shepard, later wrote, “I learned a new sound that day, a sound more horrible than description can picture – the thud of a speeding living body on a stone sidewalk.” The outpouring of grief after the deadly fire was enormous. Hundreds of thousands of people joined a funeral procession for the seven unidentified victims of the fire.

In the aftermath of the fire, labor organizers knew there was no time to waste. They held a public meeting at the Metropolitan Opera House on April 2. Rose Schneiderman, a young Jewish labor organizer, called upon working people to stand up and take action. As a result of the labor organizers’ work and the profound horror in New York over the fire, legislators began an investigation that led to new laws protecting worker safety. The Triangle Shirtwaist fire shined a light on the dark and dangerous world of early twentieth century factory labor and Jewish labor activists seized the moment to bring about desperately-needed change.

Shabbat Shalom!

שבת שלום!